The Age of the Drone

After a century of innovation, millions of drones now take to the air and warfare is changed forever.

Editor's Note: Michael J. Boyle is Associate Professor of Political Science at Rutgers Camden and a Senior Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia. His most recent book is a comprehensive look at drone technology and the risks it might bring, The Drone Age: How Drone Technology Will Change War and Peace. Portions of this essay appear in the book, published by Oxford University Press.

Rapid innovation in drone technology over the last decade has led to dozens of new commercial and scientific applications, and will change the patterns of war and peace in the future. Over ninety countries now have active UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) programs and thirty have armed drones. Although the U.S. has more drones and leads the world in terms of quality, others are catching up. According to the Pentagon, China plans to produce as many as 42,000 land- and sea-based drones by 2023.

Unlike missiles and other aerial projectiles, drones are aircraft that do not have a pilot on board and are instead controlled by someone on the ground. They are typically intended to be reused rather than simply crashed into a target. Most drones are not weapons in themselves, although they can be equipped to carry weapons of different sizes.

The US Air Force rejects the term “drone” since their highly sophisticated models are under direct human control.

While most people use the term “drone” broadly, the language around them is controversial. Within the US Air Force, for example, the terms “drones” and “UAVs” are generally rejected in favor of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) because they obscure the fact that all models are controlled by human beings, even if the pilot is not physically located in the vehicle itself. Yet the term “drone” has become dominant in public debate, becoming the catch-all for everything from large military drones to small quadcopters.

More than a century of technological innovation has brought us to where we are today. During World War I, British military officials sought to develop some form of radio-controlled aircraft that could be used as a flying bomb against the Germans. They turned to an eccentric engineer, Archibald Low, to meet the challenge. Often called the “father of radio guidance systems,” Low created innovations in guided rockets, planes and torpedoes that were so important the Germans tried twice to assassinate him.

Low’s prototype worked and showed that in-flight navigation was possible over short distances, but it was hardly a rousing success. After watching one unsuccessful test flight, a British military observer snapped, “I could throw my bloody umbrella farther than that!”

Advances followed during and after World War I, including the Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane funded by the US Navy. Elmer Sperry began experiments designed to develop an “aerial torpedo” to be launched at German U-boats and other targets. Sperry had been perfecting gyroscopes for naval use since 1896 and established the Sperry Gyroscope Company in 1910. Even though airplanes had only been flying for eight years, Sperry became intrigued in 1911 with the concept of applying radio control to them. He realized that for it to be effective, automatic stabilization would be essential, so he decided to adapt his naval gyro-stabilizers (which he had developed for destroyers) to the task.

The ability of drones to be re-used is one distinction between them and cruise missiles.

Sperry experimented with different ways to get these planes into the air, including most notably attaching the aircraft to the top of his car and driving it at 80 miles per hour down the Long Island Motor Parkway to create a wind tunnel-like effect. The airplane nearly lifted the car off the road once it hit flying speed. By March 1918, Sperry had devised a way to launch the bomb-laden unmanned aircraft via a catapult system that would allow it to fly approximately 1,000 yards and still be reused.

This issue — reusability — would later become central to the distinction between drones and cruise missiles, but in the early twentieth century, the distinction was not as clear. Many of the forerunners of drones were explicitly designed to be flying bombs. Some advocates of unmanned aircraft experimented with reusable prototypes; others worked with craft that were deliberately expendable. Many of the technical issues — remote control, precision, and payload capacity — were the same. As usual, wartime necessity forced inventers to confront these problems and develop solutions.

The US Army turned to Charles F. Kettering, founder of the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company, and to Orville Wright. Together, these men — sometimes rivals but here joined in the war effort — produced the Kettering Bug, one of the first mass-produced, widely used unmanned aircraft. The Kettering Bug was relatively small — only 12 feet long and made of wood — but it could carry a 180-pound explosive. The underlying idea was that the Kettering Bug would be able to fly approximately 75 miles to a predetermined target so long as the engineers had preprogrammed the engine to do enough revolutions to reach the target.

The Kettering Bug was the first airplane that could be both stabilized and navigated remotely through the use of pneumatic sensors and gyroscopes. The army considered developing between 10,000 and 100,000 Kettering Bugs, but in the end fewer than fifty were actually made.

The British Royal Navy also experimented along these lines, creating aircraft that blurred the lines between drones and cruise missiles. One of their experiments was the Larynx, a fixed-wing, unmanned aircraft which could fly as fast as 200 miles per hour. The early trials of the Larynx showed promise as it was able to fly 112 miles toward its target, but often crashed miles short of its ultimate destination. But only a few prototypes were made, and research on drones as cruise missiles halted for a while.

In the 1930s, government attention shifted from turning planes into bombs toward forms of remote control of a craft by radio. Both the U.S. and United Kingdom started looking for small unmanned aircraft that could be used for target practice for anti-artillery weapons. The idea was to use inexpensive drones to improve the accuracy of gunners in shooting down moving targets. In 1932, the Royal Navy introduced an early target drone prototype, called the Fairey Queen, and then took parts from two manned aircraft and created a radio-controlled target aircraft.

These de Havilland Queen Bees, as they became known, were controlled remotely by a radio signal to circle boats in the water for anti-aircraft artillery practice. They were considered so successful that eventually 400 were constructed by the Royal Navy.

The Queen Bees were influential in establishing the contours of what a drone is supposed to be — small, mobile, and reusable. And, in a play on words, they may have also given their descendants their name, since a drone bee is a male honey bee that attends the queen bee but does not gather nectar or pollen like a female worker bee.

The term “drone” derives its name from small pre-WWII planes used for target practice.

Target drones were attractive to the U.S. as well. By the mid-1930s, the Northrup company had a division wholly devoted to unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and planned to develop a thousand of their own US version of the Queen Bee, called the OQ-2A target drone.

The growing sophistication of radio technology led to the emergence of a hobbyist community devoted to tiny, radio-controlled planes. Among these hobbyists was Reginald Denny, a British émigré to the United States. Denny began his career as B-list Hollywood actor in silent films during the 1920s and continued to act sporadically until the 1960s. After founding a company in Van Nuys, California, in 1934, Denny and his collaborators came up with a prototype radio-controlled plane — nicknamed the Dennymite — which attracted the interest of the US Air Corps (later the US Air Force). In 1940, he successfully pitched the aircraft to the US Army, which agreed to buy fifty for target practice. After the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, the air force and navy also expressed an interest and that number increased to a planned 15,000 drones.

The Radioplane Models had a wingspan of nearly 12 feet, weighed 130 pounds, and later models could fly as much as 140 miles per hour. Because of the insatiable needs of the military service during World War II, thousands of Radioplane models were quickly constructed and put into service, but never anything close to the numbers the military originally planned.

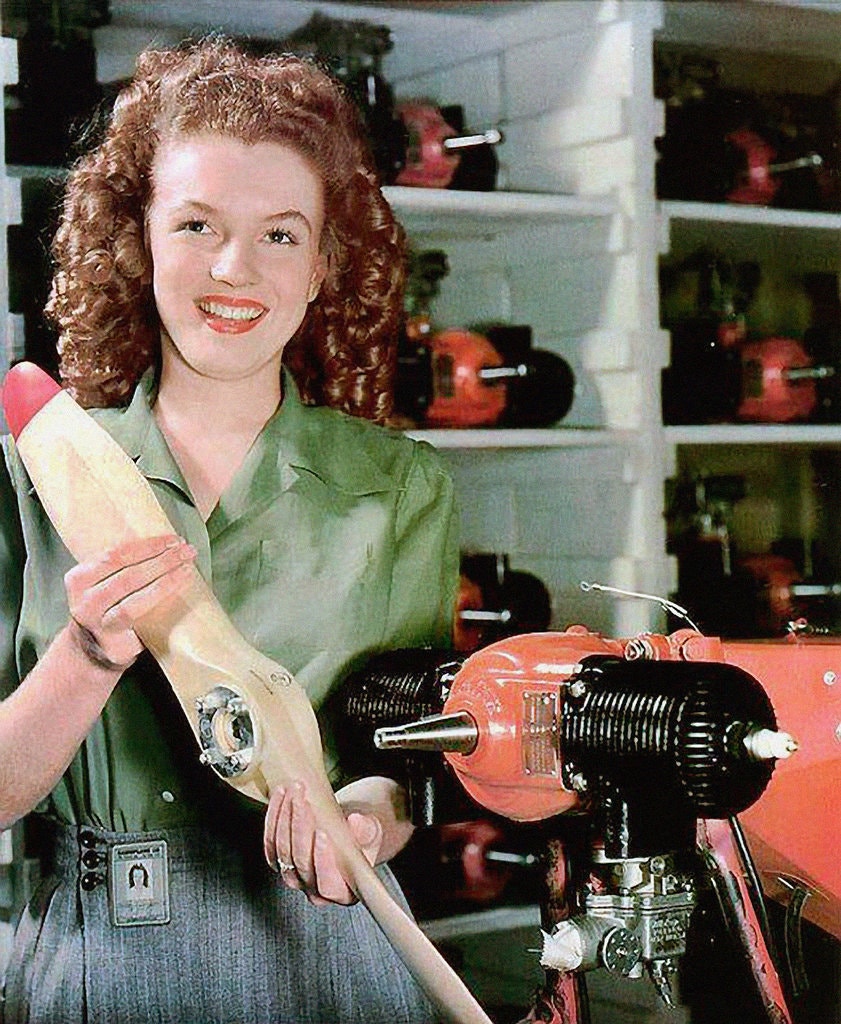

This effort drew the interest of Captain Ronald Reagan of the US Army’s First Motion Picture unit based in Culver City, California. Recognizing a good story that would aid the war effort, Reagan assigned Private David Conover to take pictures of workers on the shop floor. Conover spotted a beautiful, brown-haired woman named Norma Jean Dougherty whom he thought had potential as a model. Dougherty — who later dyed her hair blond and became known as Marilyn Monroe — was first photographed as a young model smiling with a Radioplane propeller.

Among the most important technological innovations was the adaptation of televisions for use in the next generation of unmanned aircraft in order to provide a view of target beyond the line of sight of the operator. The US Navy began experimenting with placing TV transmitters on aircraft to allow operators located in a nearby aircraft to see out its cockpit and steer it to the proper destination.

By 1941, the navy expanded this to a full-fledged, 70-pound RCA television in the drone that could transmit a picture up to 30 miles away. That picture was sent to an accompanying aircraft that could make decisions on targets. Initial tests showed that these drones could hit targets with torpedoes with remarkable accuracy even when the drone was beyond the operator’s line of sight. Navy officials soon began to work on radar technology to allow transmissions of images to the accompanying manned aircraft at night and in poor weather.

During World War II, US military production of drones involved an array of other target drones, including both biplanes and monoplanes, the efforts to convert B-17 and B-24 bombers into radio-controlled missiles, and the construction of Katydid drones which could compete

in lethal accuracy with the German V-1 rockets. Under the leadership of Lt. Commander (and later Rear Admiral) Delmar Fahrney, the US Navy developed aerial

assault drones, and even contemplated using drones to ram enemy fighters. The navy converted a TG- 2 biplane torpedo bomber into a remotely controlled drone and conducted a demonstration attack on a US destroyer. As Ann Rogers and John Hill have noted, “this can be seen as the first use of an unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV).”

In 1944, Air Force officials gradually hollowed out both B-17 and B-24 planes and transformed them into remotely-controllable cruise missiles. They packed the planes, newly dubbed BQ-7s, with 30,000 pounds of RDX explosives by stripping out every piece of payload not necessary for converting the plane into a flying missile. The biggest technological problem remained the remote control of the aircraft. While the mothership flying behind the explosive-laden aircraft could make adjustments to the trajectory of a BQ-7 in flight and even convey television pictures of the cockpit and control panel, pilots were still needed to get the drone airborne because control from the mothership was not sophisticated enough to allow for the plane to take off on its own as a truly unmanned vehicle.

This approach was tested in Operation Aphrodite, a mission to use BQ-7 drones to attack Nazi bases along the French coastline. In this mission, two airmen — a pilot and an autopilot technician — would need to be on board at takeoff to get the plane into the air and make sure it was headed toward the intended target. If all went to plan, the pilots would bail out with parachutes over the English Channel and later be collected by boat. Yet the BQ-7 drones still failed and in one test run, Joseph P. Kennedy, the older brother of the future President Kennedy, was killed when it exploded in mid-air.

During World War II, the US Navy developed radio-controlled bombers called BQ-7s packed with explosives to fly into high-value Nazi targets.

During the Cold War, drones were an important but underrecognized area of research for the U.S., USSR and others, and were put to a wide variety of surveillance tasks. But they really came into their element with the introduction of the MQ-9 Predator and Reaper drones and the RQ-4 Global Hawk in the 1990s. These models used satellite communications and GPS to allow for more adaptive remote control and long endurance for military grade drones. Even so, they are still dependent on human control and are no more automated than a commercial airliner. In fact, most large military drones are useless without a ground control station where pilots are located and a complex supply chain to ensure that the vehicle remains in the air. Because pilots are so essential, there is a vast bureaucratic infrastructure around the training and supervision of pilots during flight.

Military drones have grown in prominence but so have commercial drones, and they can vary so substantially that they hardly look like the same technology. The most famous military drone, the now-retired MQ-1 Predator, is closer to a jet like an F-16 than to the small drones employed by hobbyists. The Predator model MQ-1B, for example, has a wingspan of 55 feet, carries 2,250 pounds of weight upon takeoff and flies for 770 miles. Its larger cousin, the Reaper (MQ- 9), is similar, although it has a slightly longer range (1,150 miles). These models can be flown by pilots located in ground control stations hundreds or even thousands of miles from the drone itself and are linked by satellites to an intelligence infrastructure that enables their use.

Compare this to the ordinary quadcopter drones employed by hobbyists and small companies for basic photography and delivery of goods. The popular Phantom 3 model drone, produced by the Chinese company DJI, has a weight of 2.64 pounds and can fly at 52.5 feet per second. At most, it can be flown 1.242 miles from the operator. The Phantom 3 has a sophisticated camera, but it cannot carry a significant payload and is small enough to be carried in its operator’s hand. In general, drones like the Phantom 3 must remain within the line of sight of the operator and have a standard radio link to that person.

There have been a number of attempts to classify drones, but a classification scale originally produced by the US Air Force focused on two general characteristics of drones: their altitude and endurance. In broad terms, some models are capable of only low altitude (such as several hundred feet in the air) while others can fly at the same height as commercial aircraft (approximately 30,000 feet). Some military surveillance drones can fly at even higher altitudes, such as 60,000 feet. The endurance for each model also varies substantially, with some small hobbyist drones capable of flying only a few hours and other, military models capable of remaining in air for more than a day.

Aside from the differences in the altitude and endurance of these drones, their functions vary across the different tiers. Drones have two distinct functions: (1) the collection and recording of images and data from the external environment; and (2) the delivery of payloads, ranging from food, medicine, and commercial packages to missiles. Some drones are capable of both, while others can do only one. Most small drones are equipped to collect images and scientific data and can be used for a wide range of development activities, such as monitoring crops and environmental damage. They can also be used for reconnaissance on the battlefield.

Military drones are often capable of being put to multiple purposes. For example, medium altitude long-endurance (MALE) drones, like the Predator and Reaper models, can be used for both intelligence collection and delivery, as evidenced by their role in delivering the missiles that killed Al-Qaeda leader Anwar Nasser Awlaki.

The high-altitude long-endurance (HALE) drones, such as the Global Hawk (RQ- 4), are generally used for sophisticated collection tasks, such as advanced imagery surveillance, and they involve technology not widely available on the commercial market. Both collection and delivery models can be used for peaceful purposes (such as surveillance, scientific research, and commerce) and for military purposes (such as reconnaissance and targeted killing). In the debate over their use, it is important to keep in mind the diversity of models and functions of drones, as those most widely discussed types and missions — the Predators and Reapers used for targeted killing — are hardly typical.

It is equally important to recognize what is new — and what is not — about drones. Many of the most widely discussed characteristics of drone technology — for example, the distance between the operator of the weapon and the target and the depersonalized nature of the violence itself — have arisen before with other military innovations, such as artillery, aerial bombardment, and nuclear weapons.

Drones are slower than most forms of manned aircraft and can be less precise than a cruise missile; they are no more automatic or dependent on computers than commercial airliners. Drones can see things on the ground just as satellites can, but not necessarily at a higher level of detail. Drones are less adaptable and nimble than manned aircraft and, at present, many military drones, such as the Reaper or Global Hawk, are less likely than a manned aircraft to evade enemy fire.

Drones are a “disruptive technology” that combine characteristics seen elsewhere into a single technology that can be deployed at low cost.

What makes drones different is that they combine characteristics seen elsewhere into a single technology that can be deployed at low cost. They combine the speed and precision of a cruise missile with the durability and responsiveness of a manned aircraft. They convey images that are strikingly real and accurate like a digital camera or a satellite but are neither as small as cameras nor as removed from their subject as satellites. In doing so, drones become what is sometimes known as a “disruptive technology” and alter the strategic choices of those that have them. And today, this has resulted in a Wild West atmosphere in the field, with dozens of actors throwing out new ideas for their use.

It is hard to overstate the speed with which drone technology has emerged as a force in global politics over the last twenty years. Inside the military, the demand for drone overflights is insatiable. As late as 2000, the US military had only a handful of drones, most of which were seen as unreliable. By 2014, the total US military inventory had increased to over 10,000 drones. In August 2015, the Pentagon announced plans to increase drone overflights in conflict zones by 50% by 2019. In December 2015, the US Air Force unveiled a plan to double the number of drone pilots, but even that may not be enough to meet demand.

Governments are not the only organizations to embrace the drone age: international organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), law enforcement, private companies, and even universities are also seeking drones for a variety of purposes. The United Nations and an array of NGOs are beginning to employ them for peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. Surveillance drones have proven useful in crisis mapping, search and rescue following natural disasters in Haiti and the Philippines, and monitoring refugee camps in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic. In the United States and elsewhere, law enforcement and emergency response organizations have begun to deploy them to track suspects, to record videos of events, and even to produce heat maps which can help to rescue stranded hikers.

The rapid pace of innovation in UAV technology has also led to dozens of commercial applications. Among the most famous of these is the proposal by Amazon to deliver packages by drones. Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, has promised that seeing one of their drones in the future will be “as common as seeing a mail truck.” Small surveillance drones have now been used by real estate agents to photograph properties and by electricity companies to check for downed power lines. Farmers are also using drones to monitor their crops and check for disease. In 2015, a small Australian company called Flirtey undertook the first successful delivery of a package by drones, dropping medical supplies at a rural clinic in Virginia. While this flight was relatively

short — the drone carried the package only one mile — Senator Mark Warner (R- VA) called it a “Kitty Hawk” moment in drone aviation.

One of the many reasons why drones are spreading so rapidly to so many domains is cost. For example, the top-of-the line Predator model costs approximately $10.5 million, compared to the $150 million price tag of a single F-22 fighter jet. While new models such as the Reaper are more expensive to fly ($12-13 million) and to maintain ($5 million per year), their cost still compares favorably with manned aircraft. In general, the drones purchased for military use are vastly more expensive than those on the commercial market. Smaller commercial models, such as quadcopters capable of modest tasks like the collection of imagery, can be bought for hundreds of dollars through commercial retailers like Amazon or Best Buy.

As the price drops every year, more organizations get the ability to fly, record images, and collect data. One Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) estimate in 2013 suggested that there would be 30,000 drones in US skies by 2020. This turned out to be a wild underestimate. By 2016, the FAA predicted that “small, hobbyist UAS purchases may grow from 1.9 million in 2016 to as many as 4.3 million by 2020. Sales of UAS for commercial purposes are expected to grow from 600,000 in 2016 to 2.7 million by 2020. Combined, total hobbyist and commercial UAS sales are expected to rise from $2.5 million in 2016 to $7 million in 2020.” Another estimate suggested that 200,000 drones are sold worldwide each month. The FAA has estimated that the global market for drones will be worth approximately $90 billion between 2013 and 2023.

What impact will the rapid diffusion of drones have? It is difficult to say because of how suddenly all of this change has come. Consider the comparison with manned aircraft. The first flight was conducted by the Wright brothers in 1903 in North Carolina with a rudimentary machine that could fly only a small distance. World War I changed all of that. British, French, and German militaries poured enormous resources into making aircraft more reliable and lethal And by 1918, world-changing advances in the technology enabled dozens of new uses for aircraft including mail delivery. By 1919–1920, the first steps toward passenger aviation had been taken.

What is different about the diffusion of drones is that they have wound up in the hands of a greater number of users than traditional aircraft ever did. The spread of drones has effectively democratized the air: allowing many actors (individuals, terrorist groups, NGOs) into the skies for the first time, while enabling others long in the air (governments, private companies, the United Nations) to do things that they never thought possible.

We will soon be living in a world in which everyone can get their hands on a drone and take to the skies, for good or bad reasons. In time, we will see weak states use drones to strike against stronger ones, and other equally matched states begin to deploy drones against each other in a war of nerves. We will see non-state actors like rebel groups and terrorists use drones to attack governments and even civilian targets from the air. We will see authoritarian governments deploy drones to watch and even suppress their own population.

In the short term, the availability of drones will entrench the advantages of powerful countries like the United States, which has a vast fleet of drones that allows it to fight in a growing number of conflicts without risking the lives of pilots. At home, the availability of drones will initially work to the advantage of law enforcement and big companies like Amazon, who will use their resources to scale up drone use and take advantage of open airspace.

But in a drone age these advantages will not last forever. In the long run, latecomers to the drone age will catch up. Over time, drones will be seen as manned aircraft are today: as a technological achievement once seen as extraordinary but now so ubiquitous that most people take them for granted.