The Bicycle that Flew to France

Dubbed the Gossamer Albatross, Paul MacCready's engineering marvel revolutionized aeronautics when it became the first human-powered aircraft to cross the English Channel.

Editor's Note: Bruce Watson is a senior editor of American Heritage. This story appeared in shorter form on his website, The Attic: True Stories for a Kinder, Cooler America.

Carrying no engine, no gas, the featherweight plane takes off at dawn. To his left, the pilot sees the white cliffs of Dover. Before him stretch just sea and sky. Head down, pedaling frantically, Bryan Allen steers his plane southward. The Gossamer Albatross is on its way. Destination: France.

Ever since Daedalus and Icarus, in Greek myth, fashioned wings of wax, human-powered flight had been a lofty dream. The footage of epic failure was all too familiar. Flapping wings flumping to the ground. Multi-layered planes collapsing like a house of cards. And these were just the comical crashes. But the Gossamer Albatross was powered by more than muscle. It also flew on pure genius.

The Gossamer Albatross was powered by more than muscle. It also flew on pure genius.

Seconds after takeoff, at ten mph, cyclist Allen feels “as if I have emerged from a world of black-and-white dreams into full-color reality.” Like Lindbergh, who crossed the Atlantic with just a few sandwiches and a jug of water, Allen is flying light. His cockpit contains an altimeter, a two-way radio, and four pints of water. Allen, a lean, ripped 140 pounds, has trained for this day on a stationery bike, watching his horsepower climb on a digital readout. But can he keep an airplane aloft simply by pedaling?

For the next two hours, Allen must pedal at a steady 80-90 rpm. The slightest slacking off will drop the Gossamer Albatross within inches of the channel. Allen must also follow directions from his support crew, constantly reporting wind conditions and weather up ahead. And he must keep his lead boat in sight. The lead boat is the key. It carries the genius.

Growing up in New Haven, Connecticut during the Depression, Paul MacCready loved to tinker. “I was always the smallest kid in the class by a good bit,” he remembered. “And was not especially coordinated, and certainly not the athlete type.” Like millions of kids raised to idolize Lindbergh, MacCready soon discovered model airplanes. “Anyone who's not interested in model airplanes,” he said, “must have a screw loose somewhere.”

But while most of us were content to fly five cent balsa wood planes, sliding the wing backward for long flights, forward for loops, MacCready designed his own models. At 15, he won a national model airplane contest. His path was set, but war interrupted.

During World War II, MacCready trained as a Navy pilot but the war ended before he was commissioned. Returning to Yale, he studied physics, then earned a Ph.D. in aeronautical engineering from Cal Tech. While working as an engineer, he spent weekends in glider cockpits, soaring in silence above the California desert.

MacCready won three national soaring titles, and in 1956 became the first American to win the World Soaring Championship. Along with piloting skill, he had an ace up his sleeve. His own invention, the MacCready Speed Ring, calculated the ideal speed for prolonged flight. Today, glider pilots still use the ring.

On through the 1960s, MacCready continued gliding and designing. He was so busy that he barely noticed when British industrialist Henry Kremer offered a prize — £5,000 — to the first Icarus to fly, self-powered, a one-mile figure-eight.

Kremer first offered the prize in 1959, stipulating that the pilot and designer had to be British. Aviation designers soon tested the limits of lightness and power. Planes slid down ramps or launched from catapults. Some flew a quarter-mile, half a mile, three-quarters. . . But turning was tricky and gravity prevailed. Then in 1973, Kremer upped the prize money to £50,000 and opened the contest to designers worldwide.

Suddenly, MacCready was interested. The design challenge was inspiring, but debt accrued from a business loan gave him another incentive. “The prize equaled the debt!” he remembered. “Human-powered flight suddenly became attractive.”

Twenty minutes in, flying a steady 5-7 feet above water, the Gossamer Albatross is faltering. Headwinds are stronger than expected. Bryan Allen’s own sweat is fogging the window. Glancing over his shoulder, Allen can still see the white cliffs. He vows not to look back again. He churns on.

At 6:05 a.m., MacCready radios from the lead boat. Stronger winds ahead. One and a half hours left to reach France. The news deflates Allen. “It’s no use,” he thinks. “I’ll have to ditch.” This certainly wasn’t as easy as Allen’s last flight — in the Gossamer Condor.

Before starting, MacCready watched hawks and turkey vultures, marveling at their soaring feats.

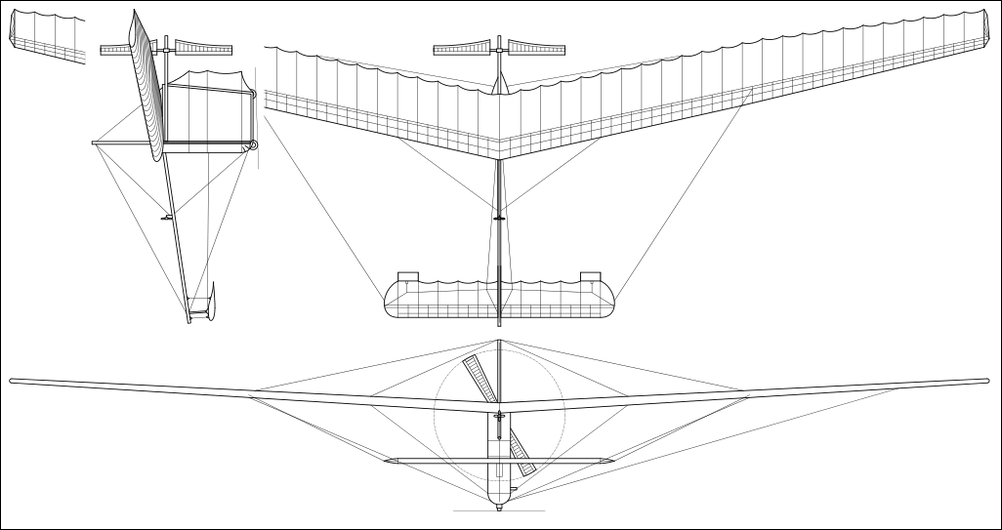

The Gossamer Condor was Paul MacCready’s first Daedalus design. Before starting, MacCready watched hawks and turkey vultures, marveling at their soaring feats. He also studied a new venture in human flight — hang gliding. Working with the co-founder of his engineering firm AeroVironment, MacCready focused on a “canard” design. French for “duck,” the canard is the reverse of most aircraft. A canard features a small fore-wing to stabilize the lift, which is provided by the much longer wing at the rear. It worked for the Wright Brothers, MacCready knew. Why not for human flight?

“Pretending I never saw an airplane before,” MacCready soon designed a craft that was part bicycle, part glider. The wings of the Gossamer Condor stretched to 90 feet, nearly as long as a DC 9’s. The cockpit was stripped — no door, barely a seat, a plastic chain hooked to a plastic propeller. Built from aluminum tubing, styrofoam, bike parts and piano wire, the Gossamer Condor weighed just 70 pounds. In 1977, on a Kremer Prize test course laid out on the flats of California’s Central Valley, Bryan Allen easily steered the craft around the figure-8. Accelerating toward the finish, the Gossamer Condor cleared a 10-foot bar. MacCready won the £50,000, paid his debt and thought he was done with human-powered flight.

6:20 a.m. Just inches above the water, Allen signals his crew. He is finished. Spent. But he must climb a little so the crew can hook the wings and save the plane. Allen sprints to 15 feet, and at that exalted height, he is suddenly soaring. At 15 feet, there is less wind, no turbulence. “I’ll try it up here for a while!” he shouts down. And on he flies.

Days after the triumph of the Gossamer Condor, MacCready learned of a new Kremer challenge. The prize was £100,000 for flying, on human power alone, across the English Channel. This would not be the first such channel challenge.

Back in 1908, just five years after the Wright Brothers’ historic flight, the London Daily Mail offered £1,000 to the first pilot to fly the English Channel. In the summer of 1909, the contest came alive. One pilot’s engine gave out early in flight. The plane ditched; the pilot was fished out of the water. The Wright Brothers planned a flight but before they could get a plane to England, a Frenchman took off.

Like MacReady, like the Wrights, Louis Bleriot was a tinkerer first class. He had already invented the first workable automobile headlamp lit by an acetylene torch. Bankrolled by this success, Bleriot turned to aviation, trying his hand at gliders, then propeller-powered planes. Several crashed. Others taxied off the runway. Finally on July 25, 1909, Bleriot flew his single-engine monoplane, at a speed of 45 m.p.h. and a height of 250 feet, from Calais, across the channel, to a pancake landing above Dover’s white cliffs. Twenty-five miles! Nonstop! But could it be done on human power?

In 1978, MacReady went back to the drawing board. Carbon fiber replaced the aluminum frame. Ribs were made of polystyrene. Mylar sheets covered the whole craft. Despite a wingspan two feet longer than the Condor, the Albatross weighed just a few ounces more.

In June 1979, the Gossamer Albatross was ready. Engineers disassembled the plane, shipped each piece to England, then rebuilt the whole craft on the coast in Folkestone. Testing. Training. Weather checks. Plane and pilot were ready. But more trouble lay ahead.

In 1978, MacReady went back to the drawing board. Carbon fiber replaced the aluminum frame. Ribs were made of polystyrene. Mylar sheets covered the whole craft.

6:30 a.m. Through his fogged window, Bryan Allen thinks he sees the French coast. But it’s only a supertanker. His water is almost gone. Dampness in the cockpit has silenced his radio, killed his altimeter. He pedals on. Thirty exhausting minutes later, MacReady reports: “We have France in sight. Four miles to go.” But Allen’s legs are cramping. He is severely dehydrated. “Altitude six inches! Six inches!” Allen digs in, thinking “Against all hope! Against all hope!”

7:30 a.m. “Gossamer Albatross,” MacCready radios. “You have one mile to touchdown!” Seconds later, the crew calls out, “Gossamer Albatross, fly into the sun.” Allen chuckles. He is Daedalus, not Icarus. No danger of flying too high and melting his wax wings. “Correction,” the crewman barks out. “Fly towards the sun.”

Coming in on wings of carbon and Kevlar, the Gossamer Albatross barely clears the rocks along the shore. Allen stops pedaling and the propeller coasts to a stop, but winds lift the plane another few feet. “Are they going to have to pull me down?” Allen wonders. Finally the breeze subsides and the Gossamer Albatross, pedaled from England to France, lands softly on the beach.

Two hours and 49 minutes aloft. Twenty-two miles in flight. Top speed 18 mph. Average altitude — 5 feet. With a boom and snap, Bryan Allen punches through the cockpit plastic and falls into the arms of a crewman. Champagne corks pop and someone hands Allen a bouquet of roses. There are hugs, handshakes for the team and its genius. “Take the rest of the day off,” MacCready tells his human engine.

Two hours and 49 minutes aloft. Twenty-two miles in flight. Top speed 18 mph. Average altitude — 5 feet.

Bryan Allen made just one more flight on his own muscle, piloting a second Albatross inside the Houston Astrodome in 1980. But Allen continued to fly hang gliders, while becoming a software engineer. He currently works for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

Paul MacCready went on to design prize winning solar planes, including the Gossamer Penguin and the Solar Explorer, which flew 163 miles, from an air base near Paris to one near London, on sun power alone. In 1987, MacReady’s design team sent Sunraycer, a solar powered car, across the Australian outback, easily winning the first World Solar Challenge. MacReady’s AeroVironment then turned to unmanned aircraft made for the Pentagon. AeroVironment is now the military’s top supplier of drones.

Before his death in 2007, MacCready earned dozens of prizes for aviation and creativity. Among these were the Spirit of St. Louis Award, the Lindbergh Award, and the National Air and Space Museum Trophy for Current Achievement. In 1999, he was named one of TIME Magazine’s 100 Greatest Minds of the Century. But while continuing to design, to dream, MacCready never missed an opportunity to speak to young tinkerers.

Turn away from those screens, he advised. Learn from nature, which has already solved most design problems. And keep your eyes on the sky. “The only big ideas I ever came up with,” he often said, “arose from daydreaming.”