Josephine Cochrane, Inventor of the Dishwasher

She did it because the servants broke the china

JOSEPHINE GARIS COCHRANE seemed to have reached the low point of her life one Sunday in about 1880, when she went to church in the midst of an illness and heard the pastor deliver her eulogy. Whatever the intent of his wistful farewell, entitled “Hoping, Waiting and Resting,” Mrs. Cochrane eventually rallied, leaving the eulogy behind and doing very little waiting, resting or hoping over the subsequent three decades of her life. She was too busy.

A few years following the illness, Mrs. Cochrane, a socialite in Shelbyville, Illinois, was putting away her best china after a dinner party when she noticed that some pieces had been chipped by the servants washing up. That too was very nearly a low point in her life, the china having been handed down for generations in the family; the legend was that it dated from the 1600s.

“Why doesn’t somebody invent a machine to wash dirty dishes?” Josephine Cochrane mused one morning. “Why don’t I invent such a machine myself?”

Mrs. Cochrane rallied again, however, and ordered that from that point forward the servants were to stand aside. She would wash the china herself. And that, as it turned out, constituted the actual low point of Josephine Garis Cochrane’s life.

No one ever hated washing dishes more, but there was no choice in the matter.

Mrs. Cochrane was just spoiled enough in her upbringing to resent the supposition that there was no choice in a matter — any matter. Nonetheless, in the case of dishes there really was no choice. “Why doesn’t somebody invent a machine to wash dirty dishes?” she later recalled musing to herself. “Why don’t I invent such a machine myself?” With that, she quit the kitchen to go into the library of her home and think. She settled into a large chair and imagined the alternatives, still holding a cup in her hand.

A half-hour later she had the idea for the first workable dishwashing machine. It recognized water pressure as the best scrubbing force and worked by spraying soapy water onto dishes held securely within a rack, not unlike the average dishwashing machine in use today.

Friends encouraged Josephine to develop her idea, and her husband probably supported it too, though he died only a few months later, leaving the fashionable widow nearly penniless. Soon afterward, she was at work in the shed behind her house, hammering pieces of hardware to a copper wash-boiler, building the first dishwasher.

“Women are inventive, the common opinion to the contrary notwithstanding,” Josephine Cochrane once said. “You see, we are not given a mechanical education, and that is a great handicap. It was to me — not in the way you suppose, however. I couldn’t get men to do the things I wanted in my way until they had tried and failed in their own. And that was costly for me. They knew I knew nothing, academically, about mechanics, and they insisted on having their own way with my invention until they convinced themselves my way was the better, no matter how I had arrived at it.”

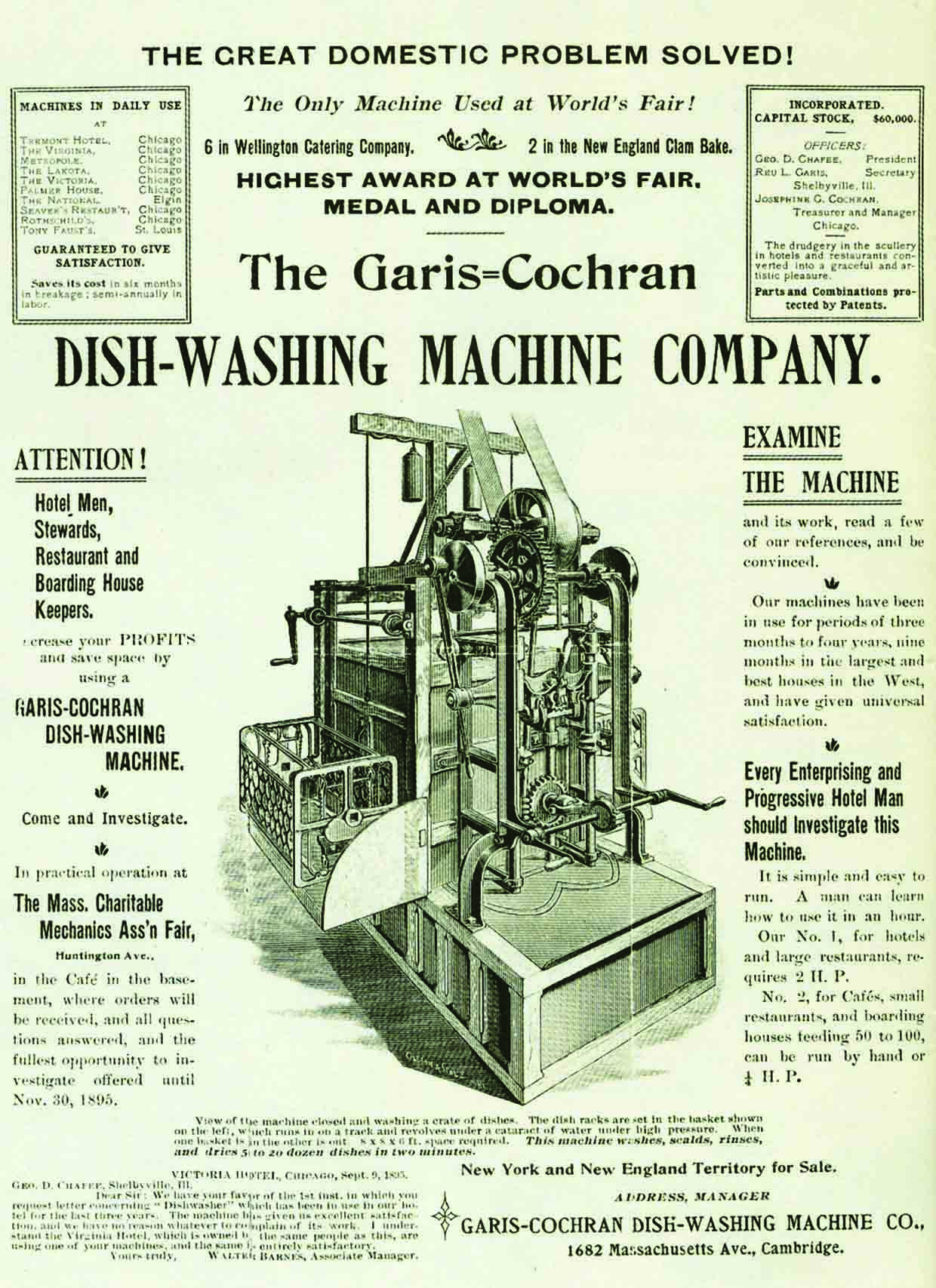

Josephine was a vivacious, a high-strung young woman who was apt to be direct in manner. Her first actual model of the dishwasher resembled a miniature sawmill, with a complication of belts and gearing. Friends and neighbors came to see the thing work, and everyone was impressed. “It is thorough in its work and simple in the arrangement required to operate it,” said one neighbor. Another called it a blessing to humanity.

Mrs. Cochrane applied for the first of her many patents on the invention and received it on December 28, 1886. Patents had been issued before for dishwashing machines, but most of them covered designs that relied on mechanical means for scrubbing, rather than on water pressure. She named her creation the Garis-Cochran Dish-Washing Machine.

With a U.S. patent and a sheaf of testimonials, Mrs. Cochrane turned to the invention of something as complex as any dishwasher: a company to market a new invention. The very qualities of stubbornness or myopia that make some people brilliant inventors often also keep them from business success. One of the first assumptions Mrs. Cochrane had made about her machine — that it was fit for the home — could easily have proved her ruination had she been stubborn about it. In the late 1800’s, homemakers weren’t ready to spend money on an expensive appliance.

Her first model resembled a miniature sawmill, with plenty of belts and gearing. Yet even the slightest maid or housewife could operate it.

Because Mrs. Cochrane wasn’t adamant about what part of humanity she would bless with the dishwasher, she traveled to Chicago in about 1887 to make another start in salesmanship, targeting institutions and hotels. Reverting to her social training, she wrote to everyone she knew in town, making mention of her dishwasher. A rich friend advised her to try the manager of the Palmer House and then introduced her to him, with the result that she received an order, and a momentous one at that. The same friend next told her to try the Sherman House, another big hotel in the city. That would have to be a “cold” sale, though, with no cozy introduction. She went to the hotel by herself and sat down in the ladies’ parlor, just off the lobby, submitting a request for a moment of the manager’s time. It was granted.

“You asked me what was the hardest part of getting into business,” Mrs. Cochrane recalled for a reporter for the Record-Herald. “That was almost the hardest thing I ever did, I think, crossing the great lobby of the Sherman House alone. You cannot imagine what it was like in those days, twenty-five years ago, for a woman to cross a hotel lobby alone. I had never been anywhere without my husband or father — the lobby seemed a mile wide. I thought I should faint at every step, but I didn’t — and I got an $800 order as my reward.”

By 1888 the company was offering two basic models, each of which could be designed in a variety of sizes. The beauty of the core assembly designed by Mrs. Cochrane for each machine was that it allowed someone other than a stevedore to operate it, as it moved crates of heavy dishes even while pumping water straight up from the bottom.

Without capital, the Garis-Cochran Company contracted for manufacture of its machines with a firm in Decatur called E B. Tait and Co. Working through a contractor proved to be a source of ongoing consternation. It isn’t uncommon for the process of transferring a new item into production to be just as demanding as inventing it in the first place. For Mrs. Cochrane it was particularly galling to have ideas and refinements disdained simply because she had no formal mechanical training. Moreover, it was vexing to notice that while she brought in the brains, the guts, and also the standing orders, Tait seemed to make all the profits.

Mrs. Cochrane never could attract outside capital to her venture. She later claimed that the only interested investors expected her to resign, as part of the deal. Her company’s big chance came with the announcement of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which would showcase the Garis Cochran Dish-Washing Machine. One restaurant manager there wrote to Mrs. Cochrane, “your machine at ‘Big Kitchen’ washed without delay the soiled dishes left by eight relays of 1000 soldiers each, completing each lot within thirty minutes… the deduction must be that this machine is perfect.”

Garis-Cochran machines cut dishwashing staff by as much as 75 percent, minimized breakage, and sanitized the dishes by rinsing with scalding water.

In 1898 Mrs. Cochrane became a bona fide manufacturer, opening her own factory near Chicago with money she had saved herself. Garis-Cochrane machines were expensive, but hotels claimed that they paid for themselves within months, reducing the number of employees on dish detail by as much as 75 percent and minimizing broken china as well. The company was beginning to thrive in the years just before her death in 1913. She died in August of that year after falling into a state of paralysis brought on by “nervous exhaustion.”

After her death the company changed names, eventually becoming known as KitchenAid. Today, KitchenAid is part of the Whirlpool Corporation, and Cochrane is proudly regarded by the company as its founder.