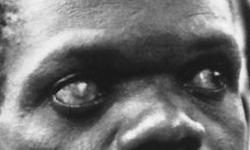

The story is so improbable it defies belief: a soil sample from Japan stops suffering in Africa. It starts when a scientist discovers a lowly bacterium near a golf course outside Tokyo. A team of scientists in the United States finds that the bacterium produces compounds that impede the activity of nematode worms. It is developed into a drug that wards off parasites in countless pets and farm animals, averting billions of dollars in losses worldwide. Extraordinarily, the drug also prevents or treats human parasitic diseases that would otherwise cause blindness and other severe symptoms in hundreds of millions of people in many of the poorest countries on Earth.

The tale depends on an international cast of thousands of scientists, medical practitioners and other dedicated participants. It also involves a company and research institute willing to give a drug away for free to rid the developing world of debilitating diseases.

Yet none of this would have happened without that soil dug up in Japan—and a healthy dose of serendipity.

The commemorative plaque reads:

The synthesis and development of ivermectin by Merck in the 1970s and 1980s provided a breakthrough treatment against infectious diseases transmitted by parasites. This discovery resulted from an international collaboration that screened hundreds of natural products to identify a promising lead compound. Merck scientists synthesized thousands of analogs of this lead and tested them. The result, ivermectin, offered a highly effective treatment for several parasitic diseases affecting a variety of animals. Following its approval for human use in 1987, Merck established a worldwide program to donate ivermectin as Mectizan® to treat onchocerciasis (river blindness), greatly reducing the prevalence of this debilitating disease. In 2015, Merck scientist William Campbell shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his role in developing ivermectin.